Greetings McDaniel students! My name is Meredith Meyers, a recent biology graduate. Dr. Jacobs, my fearless undergraduate research advisor, informed me of the blog and asked me to write an entry about my experience mapping the sea floor.

As a recent graduate, I was fortunate enough to receive a full-paid internship with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) aboard the Okeanos Explorer to participate in sonar mapping of the Northeast Canyons in the Atlantic Ocean. The Okeanos is an educational research vessel whose main mission is ocean exploration (Okeanos-primary Greek water deity; Explorer-one who travels in search of scientific information). We left Norfolk, VA on May 27th and arrived back in port in Davisville, Rhode Island on June 13th.

A nervous intern, about to board the Okeanos Explorer in Norfolk, VA

As excited as I was to be selected as an intern, I was super nervous about living at sea for three weeks! How would I react to not seeing land for that long a time? Would I get seasick? What if the food isn’t good? What if I run out of shampoo? All of these questions lingered in my head as I lugged my overstuffed duffel bag up the gangplank.

You’ll be happy to know that I adapted extremely fast to living at sea. Before we left port, I stocked up on the necessary toiletries and snacks, just to be safe. Upon meeting the other members of the science team, I quickly realized I was the “baby on board”- the youngest and most inexperienced member! Being the newbie has its perks, however. Mapping took place 24 hours a day, which meant team members had to be in the control room around the clock. I was lucky to receive the 8am-4pm shift. My fellow intern, a graduate student at Old Dominion University, was not so lucky, receiving the 8pm-4am shift.

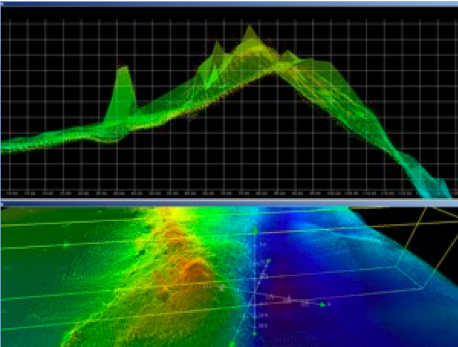

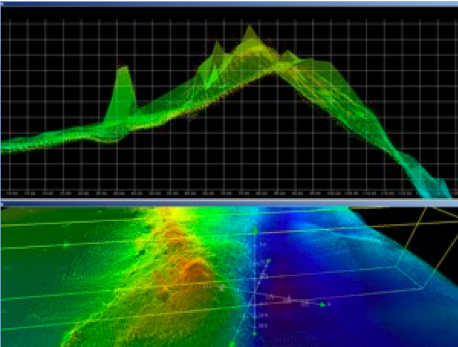

Learning the ropes of multibeam sonar mapping was smoother than I could have imagined. The science team was extremely patient in explaining how multibeam sonar works, and what my duties were during my shift. From 8am to noon, I kept log books updated and watched over the multibeam monitor to make sure the data we were collecting was usable. While mapping these canyons, the water depth changes drastically, and if the multibeam is not compensated for these changes, the data will be useless. From 12:30 to 4pm, it was my turn to clean the data we were receiving in a program called CARIS. A picture of what canyon data looks like in CARIS lies above (terrasond.com). My primary job was to search for and remove “outliers” in the data-points that were simply out of place and were clearly not a part of the data set (a school of fish for example). Being able to view the topography of the ocean floor, literally as you float above it, was an incredible experience.

Learning the ropes of multibeam sonar mapping was smoother than I could have imagined. The science team was extremely patient in explaining how multibeam sonar works, and what my duties were during my shift. From 8am to noon, I kept log books updated and watched over the multibeam monitor to make sure the data we were collecting was usable. While mapping these canyons, the water depth changes drastically, and if the multibeam is not compensated for these changes, the data will be useless. From 12:30 to 4pm, it was my turn to clean the data we were receiving in a program called CARIS. A picture of what canyon data looks like in CARIS lies above (terrasond.com). My primary job was to search for and remove “outliers” in the data-points that were simply out of place and were clearly not a part of the data set (a school of fish for example). Being able to view the topography of the ocean floor, literally as you float above it, was an incredible experience.

One member of the science team, David Packer, planned on using the data we collected in order to identify deep sea coral habitat within the canyons. Working for NOAA’s Northeast Fisheries Science Center, he hopes to conclude that these canyons serve as prime habitat for deep sea corals, and to begin the process of naming these canyons as marine protected areas. I interviewed Packer for the Okeanos Explorer website. The full story of his mission can be found here: http://oceanexplorer.noaa.gov/okeanos/explorations/acumen12/1204_interview/welcome.html

While onboard, I had to learn the nautical lingo. Starboard side was the right side, port side was the left, the stern was the back of the boat and bow was the front, forward meant toward the front, and aft meant toward the back. Frequently we had to contact the bridge during our shifts in order for NOAA Corp officers to position the ship where we needed to map. We had to don a headset with a microphone, and call the bridge using a switch board saying “Bridge, this is survey…” (survey is lingo for control room). We also had to use phrases like “Copy that”, “Roger”, and “back deck is secured”. At first I felt silly, like I was in the military, but after the first few days these phrases became second nature.

So that was my job during my shifts! During my time off was a different story!

I shared a stateroom with another member of the science team, who recently received her PhD from the University of Delaware. We each had a bunk and a large closet, and our room was complete with our own bathroom. Additionally, our room was equipped with Direct TV, so we were never without our favorite TV shows. Our evenings consisted of Friends, Seinfeld, and Family Feud.

Meals onboard the ship were absolutely incredible! Three cooks served us hearty breakfasts, lunches, and dinners every day. Breakfast consisted of French toast, pancakes, or Belgian waffles, bacon, sausage, ham, and hash browns. If you wanted eggs, you simply took your plate to the kitchen door, informed the cook how many and how you wanted them cooked, and waited for your name to be called when they were ready. Lunches varied-pizzas, burgers and hotdogs, Reuben’s, tacos, and Swedish meatballs (one of the chef’s favorites). Dinners varied as well. Italian night consisted of ravioli and veal parmesan with homemade garlic bread, Chinese night with homemade fried rice and low mien, and our last meal was steaks and King crab legs. Homemade chocolate chip cookies were always on hand, and a freezer in the pantry was fully stocked with ice cream whenever you wanted.

Once a week, we had to participate in emergency drills. The first drill would be a fire drill, followed by an abandon ship drill. An officer would come over the intercom saying, “This is a drill, this is a drill, this an abandon ship drill”. We were required to grab a ball cap, a long sleeved shirt, long pants, our life jacket, and our survival suit (nicknamed Gumby suit because you literally look like Gumby). Once on deck, roll was called and we had to prove to the NOAA Corp officers that we could don our Gumby suits in 1 minute-easier said than done! Once the drill was complete, we could return to our regularly scheduled programming.

The weather was beautiful for most of the trip. Sunny skies and mid 60 degree temperatures made for comfortable outings on deck. Dolphin sightings in the morning and afternoon became the norm, and we were lucky enough to catch a humpback whale one morning. Occasionally, we would set up camp chairs on the fantail (back deck) and eat dinner. On Tuesday and Friday nights, we would drape a sheet over the ROV hanger on the fantail and watch a movie (The Muppets was my favorite!). One night we discovered the sea had turned neon green due to the bioluminescence of the plankton.

Sleeping onboard was never a problem either! The gentle heave and roll of the ship on the waves rocked you to sleep. In fact, the first night back in port I slept horrible because I was simply stationary. Tropical storm Beryl did cause the team one miserable night. The waves were so rough it was impossible to sleep. You were literally airborne while lying in your bunk, your personal items falling off your dresser, and your door flying open and slamming shut again in the middle of the night. Needless to say, the data collected that night were useless. But one night out of nineteen isn’t bad!

The day we pulled into port was a depressing day. I had loved living at sea. Being away from the hustle and stress of the real world was liberating, and being on the ocean is definitely where a marine biologist belongs. Shortly before we docked, our leader Meme told me I should go up on deck because land was insight. Disheartened, I declined saying I’d rather be back at sea. That night we went out to dinner and toasted our successful cruise, and sadly said our goodbyes to each other the next morning.

Now, as I search for graduate schools in the coming future, I am so thankful I was given the opportunity to participate in this expedition. It opened a whole new door and is shaping my visions for grad school and career paths. I realized I would be happy and content to be at sea frequently, and this conclusion was sealed when tears fell as I left the ship. I am know considering deep sea biology as an option for grad school, as well as earning my certificate in ocean floor mapping, in order to participate in future expeditions.

Pheww…you’re probably exhausted from reading this entry. I guess when you’re passionate about something it’s easy to get carried away. NOW McDaniel students: I challenge YOU to find your passion. Study hard, work hard, persevere! Nothing important ever comes easy. Try new things, especially the things that scare you, and take chances! That’s where I found my passion-on the open ocean.

“We lose ourselves in the things we love. We find ourselves there too.”

The science team of the EX1204 on the fantail. I'm in the "L"!!

Full picture of the Okeanos Explorer at sea! (moc.noaa.gov)