I love attending lectures on campus, and my favorites are always the ones sponsored by our English department. On Tuesday evening, I had the pleasure of attending the annual Holloway Lecture, where I got to listen to Princeton professor Bill Gleason give his talk, “Masterpiece Theater Revisited: Nathaniel Hawthorne and the Pulps.”

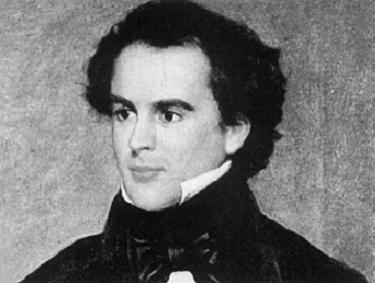

I have to admit that prior to attending this lecture, I wasn’t sure if I was going to like it. I read Hawthorne’s The Scarlet Letter in high school and I’ve read one or two of his short stories, but they didn’t particularly captivate me. Beyond this, I didn’t really know a lot about Nathaniel Hawthorne.

However, I always go to lectures with an open mind, and Bill Gleason’s lecture has made me reconsider Hawthorne in a new light. I am now more interested in reading Hawthorne’s work than I had been before. (When I take the English department’s Edgar Allan Poe class next semester, I might try to write a paper about Poe and Hawthorne’s works.)

Gleason discussed how at Princeton, he and one of his first year seminar classes were looking through old dime novels and pulp magazines from the 1920s and 1930s when they noticed that an April 1938 issue of one of the magazines, Weird Tales, featured a republished Hawthorne story called “Feathertop.” This intrigued the group. Why was a magazine called Weird Tales publishing a story from the esteemed Nathaniel Hawthorne, and what did it say about the readers of the magazine and the stories themselves that “Feathertop” and several other Hawthorne stories appeared in Weird Tales?

Gleason argued that the literature we view as “classic” isn’t classic because of its timeless excellence. Instead, works become “classic” because people of certain eras pick them up and say that they’re excellent. In other words, literary canonization is dependent on the historical moment. What works are considered “classic” changes over time.

It only took Hawthorne about a decade before his work started to gain serious interest in literary circles, and it’s remained popular in such circles ever since. But early 20th century magazines aren’t “high culture”–they’re “low culture.” What was a high culture piece of work like Hawthorne’s story doing in a low culture publication? In “Feathertop,” a witch, Mother Rigby, brings a pumpkin-headed scarecrow to life. The scarecrow, named Feathertop, goes to town, and for a while, people think he is a delightful gentleman and are somehow unable to recognize that he has raggedy clothes and a pumpkin head. Gleason argued that “Feathertop” captivated readers because it is an allegory of the creative process and a satire of the process with which literary circles decide what works they like, in addition to being a social satire of “cultural elites.” These class-related satirical elements, combined with a somewhat spooky subject matter, were sure to delight most Weird Tales readers.

I would have never thought that Hawthorne stories would be spooky or that they might have appeal outside of literary circles in the same way that Poe’s tales have a lot of appeal. Now that I have some insightful new ways to think about Hawthorne’s works, I might someday explore them on my own. Gleason’s lecture, as well as many of the English and literature classes I have taken at McDaniel, has prepared me to do just that.

Leave a Reply