Andrew Wyeth, Wind from the Sea

1947

Egg tempera on canvas

47cm x 70cm

National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

Provenance:

Sold January 1948 to Clay Bartlett in Manchester, Vermont; sold February 1952 to Charles Hill Morgan in Amherst, Massachusetts; gifted from his estate in 2009 to the National Gallery of Art, D.C.[1]

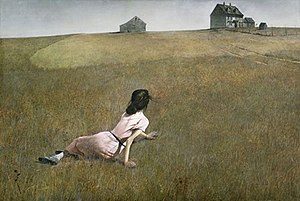

A window frame extends past the left boundary of the canvas. Through its muted, gray-brown frame, a breeze travels inward and lifts decorated but ragged curtains past the bottom of the border of the painting and into the viewer’s space. A dark, dirty and cracked shade covers the top section of the window pane. The landscape outside, which consists of a plain field of dying grass and a worn road, recedes backward to a far-away strip of trees and a sliver of water under a colorless sky. This is the view from a dormer window on the third level of Christina and Alvaro Olson’s house in Cushing, Maine, and it holds more meaning than is immediately visible. When opening the pane to cool down the room, the incoming sea breeze lifted the curtains in such a way that Andrew Wyeth was instantly inspired.[2] In his rush to remember this fleeting moment, he sketched it over top of a different image—a study of Christina Olson staring off into the distance. He then spent months refining and creating the final piece.[3]

Despite the painting’s lack of human figure, this paper will suggest that Christina Olson is the subject Wyeth truly depicts in Wind from the Sea. The two were introduced by Betsy James, Wyeth’s future wife and Christina’s longtime friend.[4] Christina, affected by a degenerative muscle disease that left her unable to walk, was taken care of by her brother Alvaro as the two made a meager living selling eggs and produce.[5] Because they lived in poverty, and Christina was disabled, their house and farm fell into a derelict state as the property became dirty, uninsulated, and in disrepair, explaining the poor physical condition of the window portrayed. Despite these conditions, Christina held onto her pride. She moved around the lower floor of the house by rocking a chair to move it and succeeded in cooking, sewing, and doing other chores.[6] While outdoors, she moved using her arms and tended to a small garden. There was a tenacity in Christina that Wyeth admired. Along with his many studies and paintings of the Olson property and house, Christina was his muse, and he painted portraits of her to capture her complex character.

Wind from the Sea, despite containing no figural image, can be read as a portrait of Christina Olson. The degeneration of her body is echoed in the decay of the painting; the upper shade and the left wall cracks while the lace drapes fray at the end, showing tears that end and disrupt the crocheted patterns. Painted by Wyeth with muddled browns and grays, the wood sits sun-bleached and aged. Christina is similarly worn, and her body, aging and misshapen, displays all the hardships she has faced. It is not difficult to see her wrinkles, bony limbs, and blotchy skin in portraits such as Miss Olson and a Kitten (1952) or Christina Olson (1947). The glass, too, is smudged underneath what remains of the grimy curtains and shade. No care has been put into this building’s repair and the neglect shows. Thus, Christina’s living conditions are readily visible and reflect her physical decline. Part of this decay is the drapery, which is not just a solid and rotting but thin lace, fragile and susceptible, just as Christina is physically weak and relies on the help of others. Outside, the grass withers and the water—a source of life—is small and distant.

Miss Olson and a Kitten, 1952

Christina Olson, 1947

Decorated with crocheted birds and flowers, however, this lace curtain is more than just fragile. It is feminine and “delicate as the real Christina”[7]; age has not stripped it of its beauty. The wooden frame is aged but sturdy. The stiff horizontals, sharp angles, and solid beams mirror Christina’s core strength of character; her fortitude was unmatched.[8] Both, stripped of embellishments, exist as their genuine selves. A sense of pride is shared by Christina and this window, as both are “still standing” despite adversity. More importantly, they do so unapologetically. Though in disrepair, this window is not sunken or broken, but stands firm and functional. Christina was keenly aware of her challenges in life but remained strong, so much so that Wyeth considered her moral fiber comparable to that of a queen.[9] The road outside indicates movement and action, something Christina did not allow her disability to keep her from.[10]

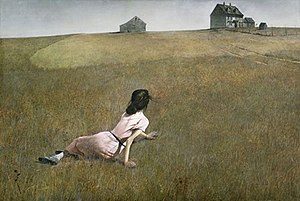

Christina’s World, 1948

Wind from the Sea is a symbolic, interior portrait of Christina Olson. The viewer is not on the outside looking in, as is the case in Christina’s World (1948). In Christina’s World, there is an air of mystery around her figure that leaves open questions of where she is, what she feels, and why her body is the way it is. These are questions posed by a composition from the view of an outsider. Wind from the Sea, however, is a view from the inside looking out; it is an interior view wherein the content of Wind from the Sea answers the question of who Christina is. She is someone fragile, damaged, and coarse, and yet she is also someone resilient, elegant, and proud. Wyeth depicts the genuine complexity of a human character without including a human body, telling the audience that Christina’s spirit remains a force to be reckoned with, just as lively and inspiring as the wind that blew in from the sea.

Bibliography

Anderson, Nancy K., and Brock, Charles. Andrew Wyeth: looking out, looking in. New York: Distributed

Art Publishers, Inc, 2014.

“Andrew Wyeth.” Andrew Wyeth. Accessed November 23, 2018. http://andrewwyeth.com/timeline

Geselbracht, Raymond H. “The Ghosts of Andrew Wyeth: The Meaning of Death in the Transcendental

Myth of America.” The New England Quarterly 47, no. 1 (1974): 13-29. doi: 10.2307/364325.

McCord, David. Andrew Wyeth. Meriden: The Meriden Gravure Company, 1970.

Meryman, Richard. Andrew Wyeth: a secret life. New York: HarperCollins Publishers, 1996.

Meryman, Richard. “Andrew Wyeth.” Life Magazine, May 1965.

“Wind from the Sea.” National Gallery of Art. Accessed November 23, 2018.

https://www.nga.gov/collection/art-object-page.143926.html

“Wyeth, Andrew.” Benezit Dictionary of Artists. 2011.

https://doi.org/10.1093/benz/9780199773787.article.B00199589

Wyeth, Andrew, Thomas Hoving, Katharine Stoddert Gilbert, and Joan K. Holt. “Two Worlds of Andrew

Wyeth: Kuerners and Olsons.” The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin 34, no. 2 (1976): 1-192. doi:10.2307/3258845.

[1] “Wind from the Sea,” National Gallery of Art, accessed November 23, 2018. https://www.nga.gov/collection/art-object-page.143926.html

[2] Nancy K. Anderson and Charles Brock, Andrew Wyeth: looking out, looking in. (New York: Distributed Art Publishers, Inc, 2014), 19

[3] Andrew Wyeth, Thomas Hoving, Katharine Stoddert Gilbert, and Joan K. Holt, “Two Worlds of Andrew Wyeth: Kuerners and Olsons,” The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin 34, no. 2 (1976): 145, doi:10.2307/3258845.

[4] “Andrew Wyeth,” Andrew Wyeth, accessed November 23, 2018, http://andrewwyeth.com/timeline

[5] Richard Meryman, Andrew Wyeth: a secret life. (New York: HarperCollins Publishers, 1996), 8-12

[6] Ibid

[7] Nancy K. Anderson and Charles Brock, Andrew Wyeth: looking out, looking in. (New York: Distributed Art Publishers, Inc, 2014), 21

[8] Andrew Wyeth, Thomas Hoving, Katharine Stoddert Gilbert, and Joan K. Holt, “Two Worlds of Andrew Wyeth: Kuerners and Olsons,” The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin 34, no. 2 (1976): 141, doi:10.2307/3258845.

[9] Richard Meryman, “Andrew Wyeth,” Life Magazine, May 1965, 102.

[10] Richard Meryman, Andrew Wyeth: a secret life. (New York: HarperCollins Publishers, 1996), 8-12

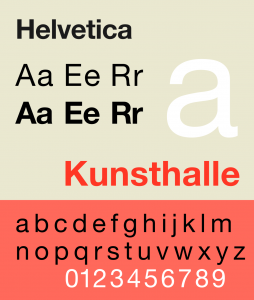

least) western society. Originally named Neue Haas Grotesk, it was created by Swiss typeface designers to match the resurfacing interest in sans-serif fonts and to promote a new age of modernism. And damn if it didn’t do its job well. American Apparel, Target, AmericanAirlines, Toyota, Jeep, JC Penny, Crate&Barrel—these are just a few of the many companies that use Helvetica for their logos. Countless street signs, posters, and websites utilize it.

least) western society. Originally named Neue Haas Grotesk, it was created by Swiss typeface designers to match the resurfacing interest in sans-serif fonts and to promote a new age of modernism. And damn if it didn’t do its job well. American Apparel, Target, AmericanAirlines, Toyota, Jeep, JC Penny, Crate&Barrel—these are just a few of the many companies that use Helvetica for their logos. Countless street signs, posters, and websites utilize it.