I was definitely wary of a reenactment game at first, especially one focused around American Art in the 1930’s. This was a period I knew little about, and as if that weren’t bad enough, I was still pretty shaky on defining socialism, communism, and other political movements that had such a strong impact on American Art. Luckily I feel that I have a more solid grasp on the subject after being put through the wringer. American Art of the 1930s, easier to define now in the “future” than during its time period, revolved around a diversity of styles that, ultimately, all attempted to be relatable to the viewer and act as a source of pride. Today the picture is much fuzzier.

Major art movements have a European-centric vein running through them. Across the sea it was very organized–a linear progression of one movement influencing the next, which would influence the next, and etc. I view that as a starting point from which American Art grew. It drew inspiration from the European vein, taking at different points, but ultimately evolving into a tree of its own. It grew and branched in different directions, all aiming high and hoping to support its own organism–the American collective and the good of the people, whether this be through calling out injustices or giving the worker his deserved recognition. Largely unattached from the roots, some movements (the Harlem Renaissance, for example) were built amid this expansive of diversity and had their own communities to foster.

While trying to pin down the art of the 1930s is difficult, it pales in comparison to defining artistic movements while living in them. The world is globalized and social media challenges what is and is not “American.” Does it have to be created in America to be American? Can an American living in Berlin, or a Nigerian living in America still create American Art? Many Americans have lost their pride and can offer no solutions. Many documented Americans would rather not identify as such. I hate how intangible the definitions of art are during the present (I don’t really, I revel in the glory of the unknown, but it still frustrates me to no end), and I genuinely cannot offer any answers.

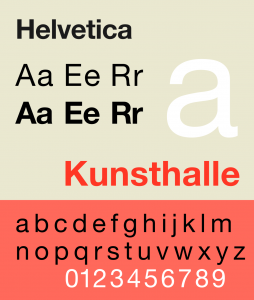

least) western society. Originally named Neue Haas Grotesk, it was created by Swiss typeface designers to match the resurfacing interest in sans-serif fonts and to promote a new age of modernism. And damn if it didn’t do its job well. American Apparel, Target, AmericanAirlines, Toyota, Jeep, JC Penny, Crate&Barrel—these are just a few of the many companies that use Helvetica for their logos. Countless street signs, posters, and websites utilize it.

least) western society. Originally named Neue Haas Grotesk, it was created by Swiss typeface designers to match the resurfacing interest in sans-serif fonts and to promote a new age of modernism. And damn if it didn’t do its job well. American Apparel, Target, AmericanAirlines, Toyota, Jeep, JC Penny, Crate&Barrel—these are just a few of the many companies that use Helvetica for their logos. Countless street signs, posters, and websites utilize it.