In the late 1970s, after the end of the Cultural Revolution and Mao Zedong’s death, China saw many reforms. The nation opened up to the world and embraced “capitalism with Chinese characteristics.” This shift saved the CCP from losing power like many other communist parties in the late 1980s and early 1990s, but artists have acquired status that likens to peasants. Many were unfamiliar with the dynamics of a market economy, finding it difficult to make a living with dwindling financial support from the state (the tiehua factory in Wuhu, for example, was eventually closed). Additionally, after the Tiananmen Square protests, the government clamped down on freedom of expression, harming the more personable nature of art. Now, some speculate that both the free market and government act together to constrain artists and reduce their work to a meaningless capital or a way to show China’s greatness, though some resistance inherently exists.

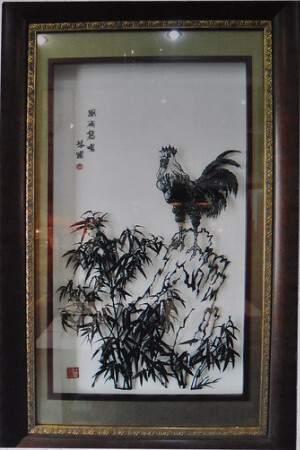

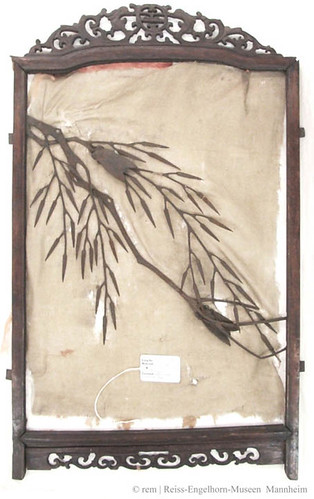

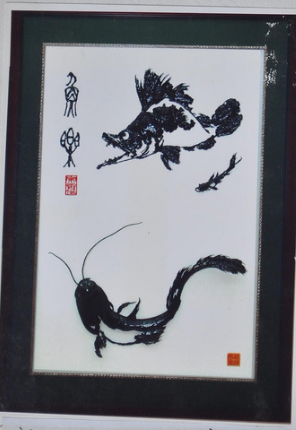

Realist Rooster, Traditional Bamboo

Characteristic of contemporary tiehua, this piece is a mix of new and old–more traditional bird-and-flower style bamboo combined with a realist rooster. In modern China, artists have managed to enrich Chinese art with outside influences while still maintaining its Chinese identity. The rooster is a newer element first popularized during the days of socialist realism, but elements go back to history. The artist could be nostalgic for both influences.

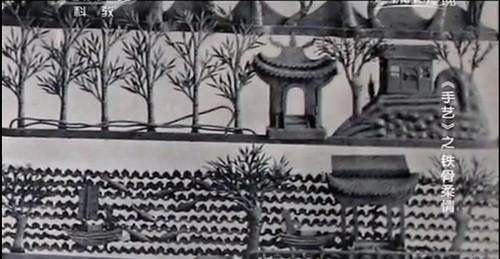

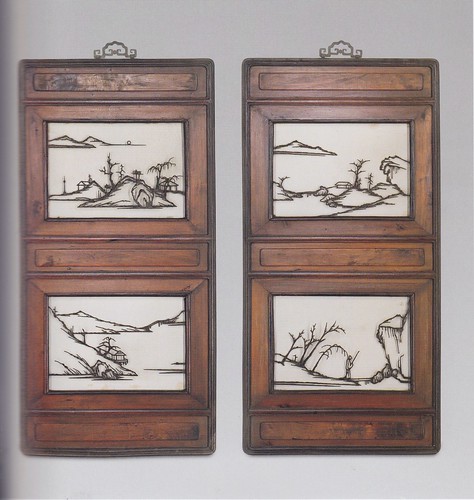

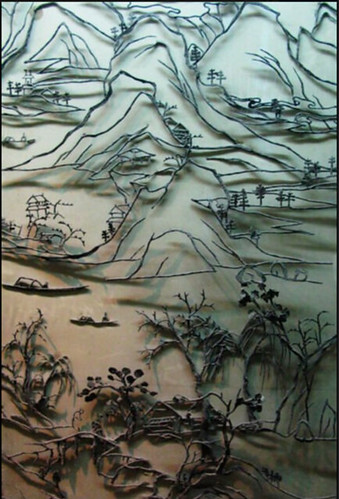

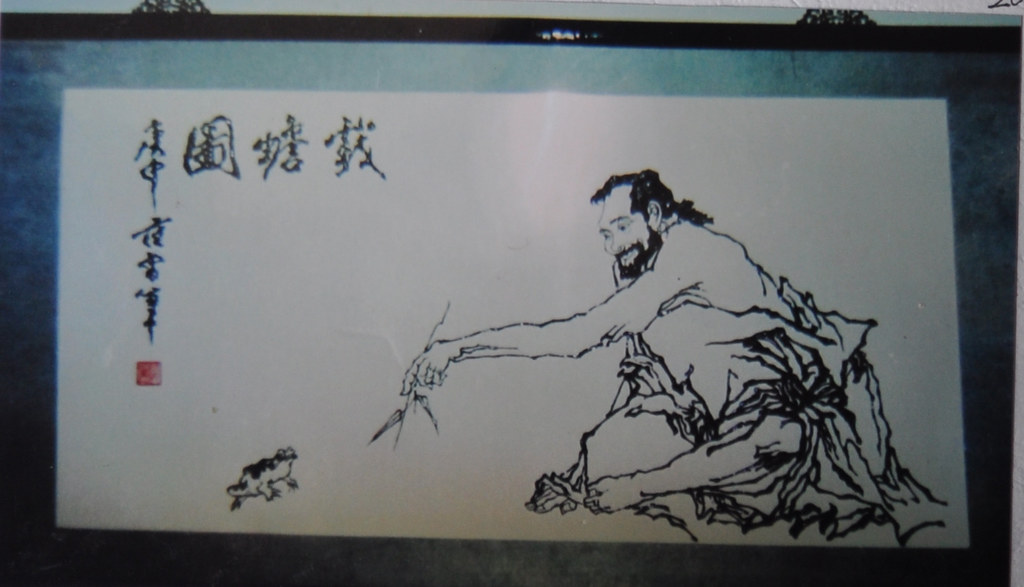

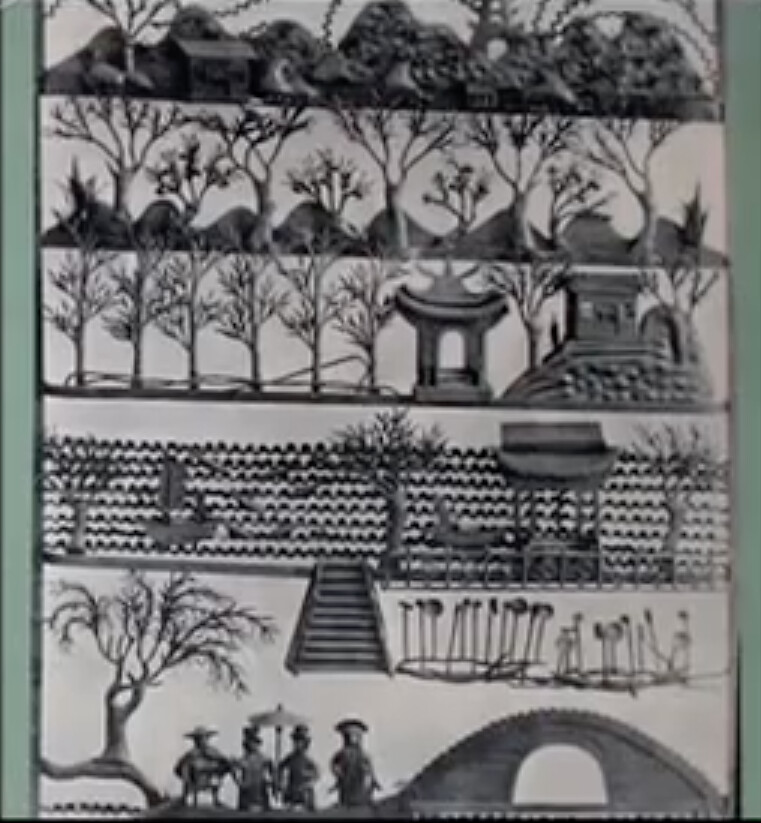

Contemporary Interpretation of Song-Style Landscape

This contemporary piece very clearly resembles landscape paintings of the Song dynasty. An important element of Chinese art that has been tolerated in new Chinese art is a clear return to tradition. Previously, the party allowed only socialist realism in the public eye, and still supports realism as an official state style. This artist resists this through his/her citation of Song-Era elements.

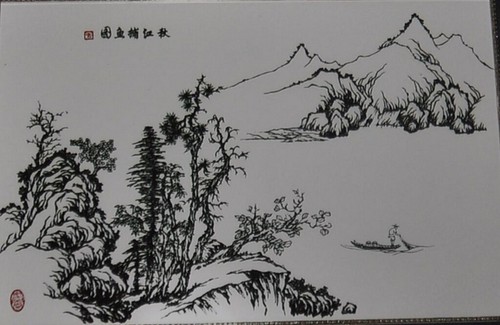

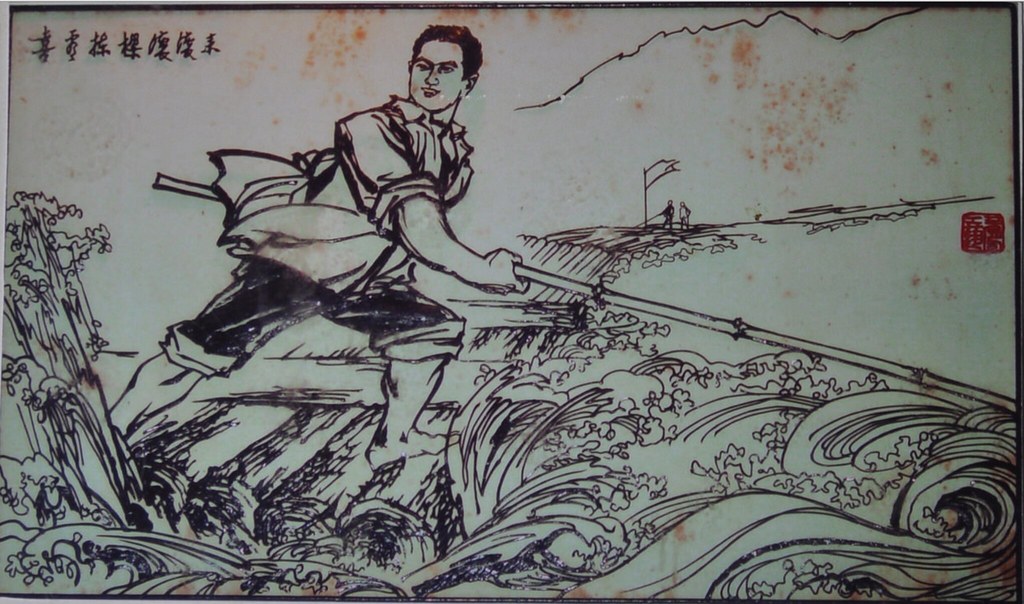

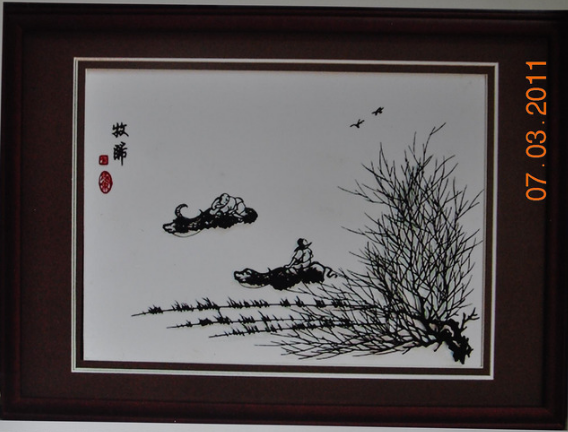

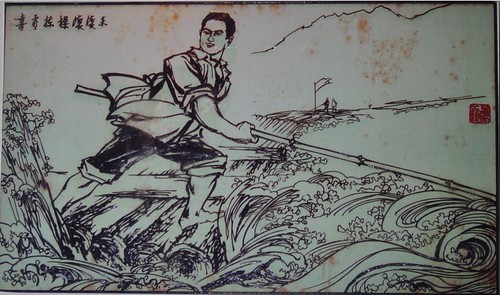

Working Class in Detail

This tiehua depicts the working class–which was popularized especially during the socialist-realist days. Nonetheless, tiehua historically found a place in various levels of society. This image would (and still can) appeal to the rural working class, or even peasants. Interestingly, artists now struggle in China and themselves have status akin to that of old peasants. Take note, however, of the blending of man and nature.

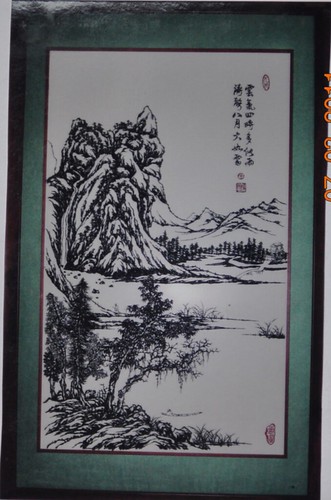

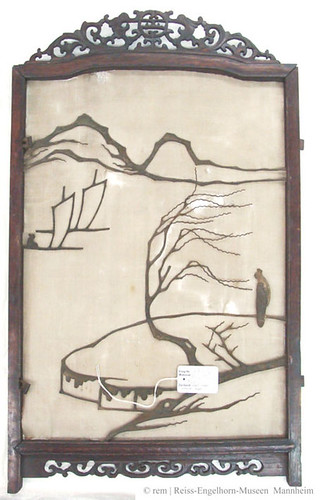

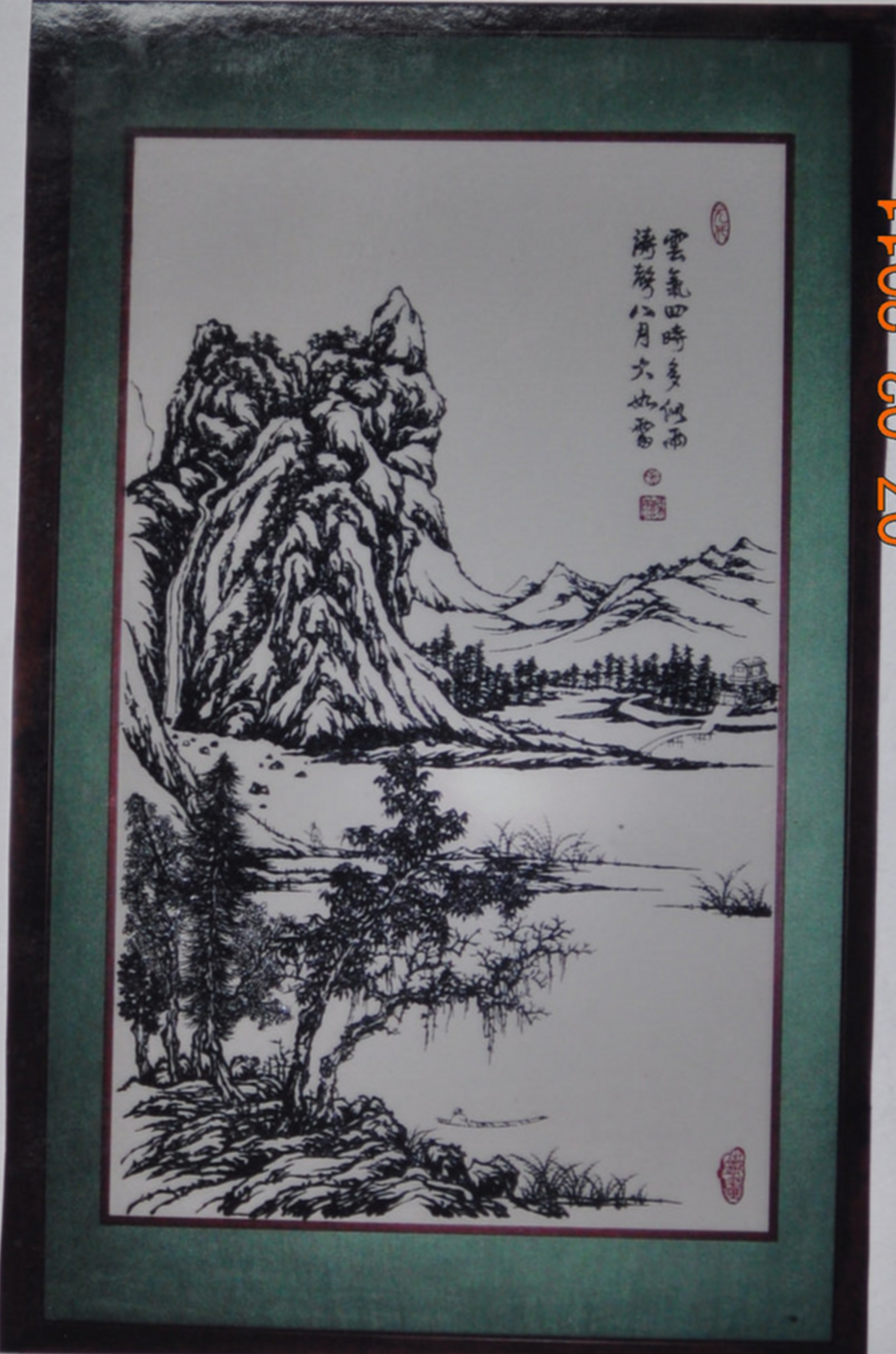

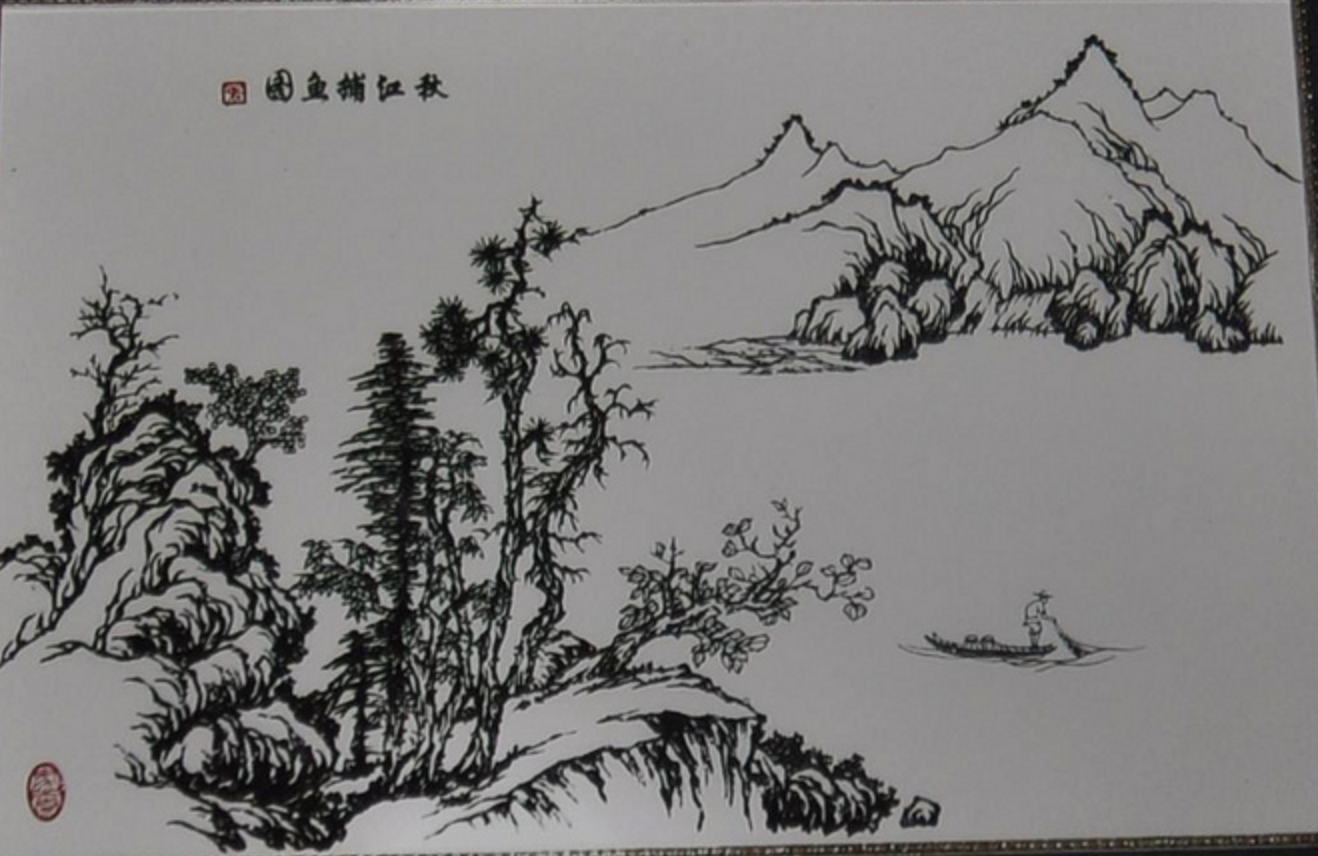

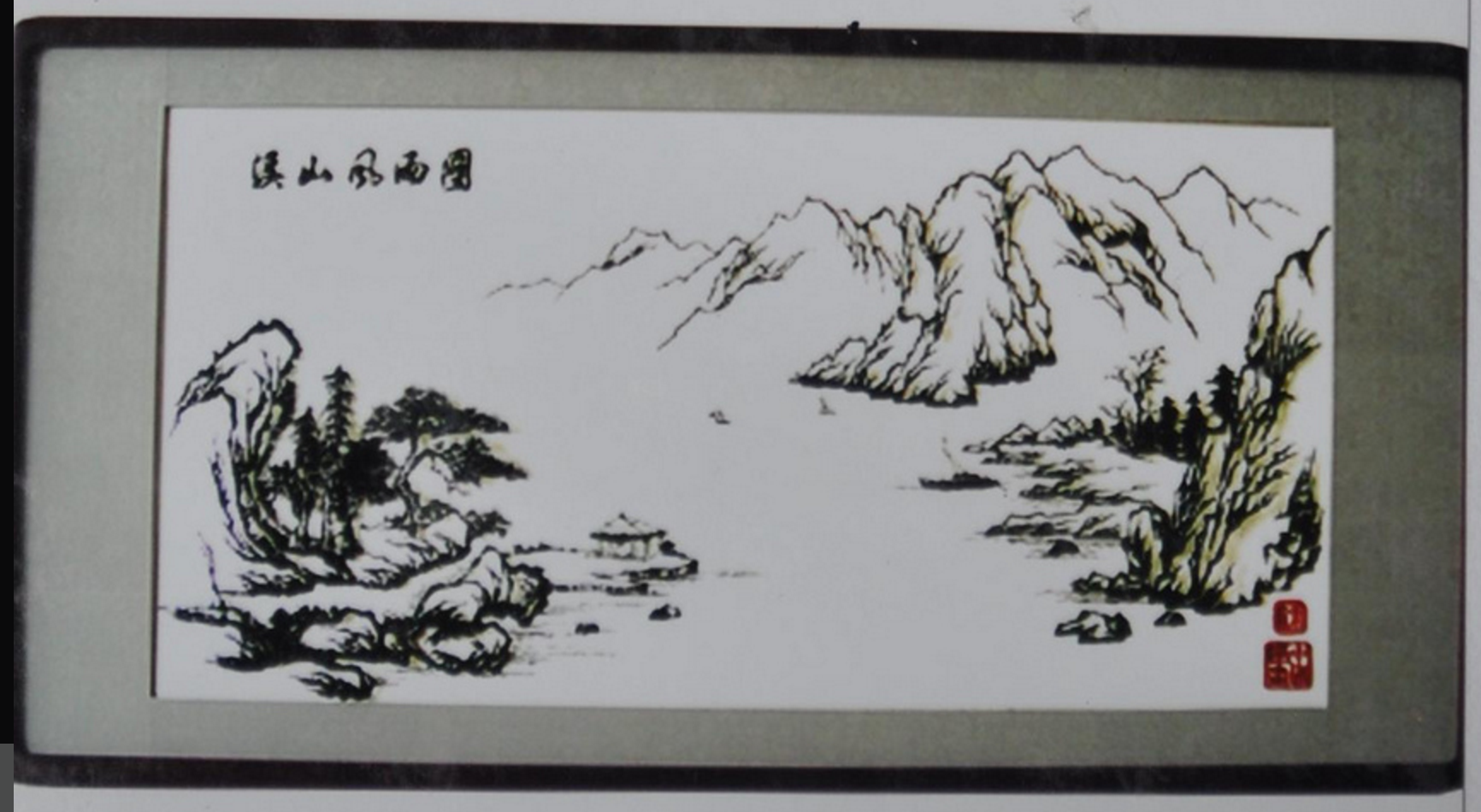

Real to Cosmic

This piece is especially influenced by traditional Chinese ways. Artists have both looked around the world and around Chinese history for inspiration. Here, the iconic ‘distant mountains’ element is present, along with a simple, flourishing natural foreground. Most notably a manis in the center fishing in what seems to be nothingness. It’s possible that this symbolizes a transition between the real world and the cosmic world–a reflection of old spirituality that would once be strongly discouraged by radical CCP members.